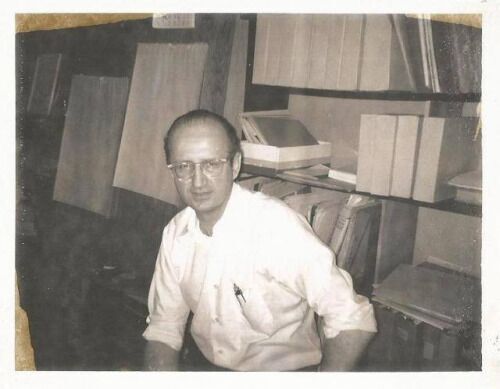

Steve Ditko the man is an enigma. Steve Ditko the creator of characters is a legend and Steve Ditko the artist remains equal parts inspiration and frustration.

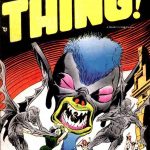

Although Ditko is known for his incredible skill as a penciller, his angular vision, unique characterizations and amazing line work, he began his storytelling career as an inker. Following his goal to be a comic book artist, Ditko began teaching himself the basics of drawing until he discovered that his earliest influence, Jerry (Batman) Robinson, was teaching at the now legendary Cartoonists and Illustrators School. Ditko promptly enrolled and quickly stood out from his class with his drive and ambition.

Robinson then recommended him to Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who hired the young Ditko as an assistant to artist Mort Meskin. Ditko’s first Simon & Kirby jobs were as a background inker, but the experience shaped his talent and taught him that storytelling and creation were just as important as artistic ability. These influences and, more importantly, the stories of how Simon, Kirby and Robinson had been ripped off by others that he would have heard, influenced his career. It was his idol, Robinson, who first introduced newcomer Ditko to a young Stan Lee, setting both men on a path that would help define their lives.

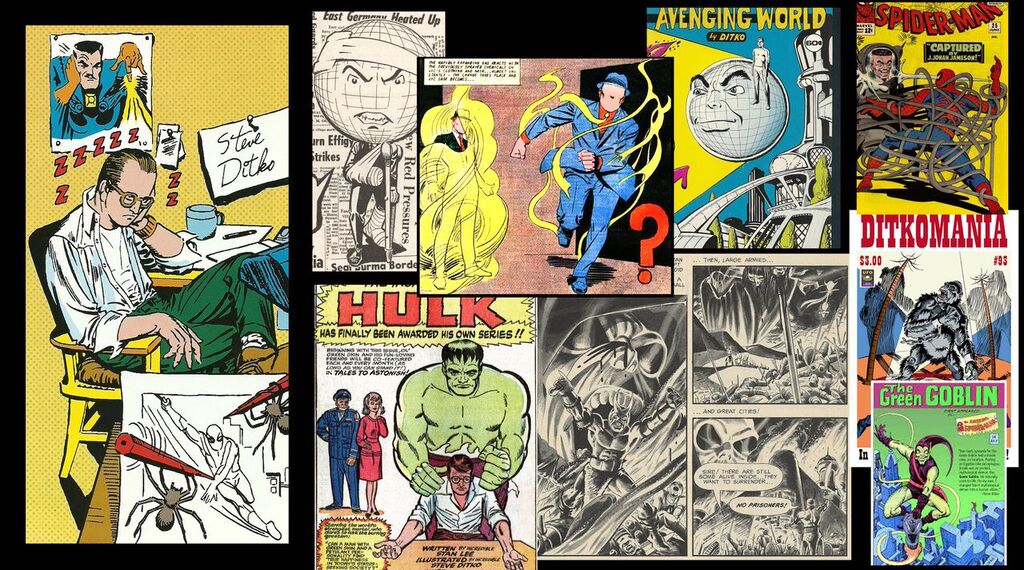

Technically the first published Ditko drawn story was a six-page romance for Gilmor’s Daring Love in 1953 and then he quickly moved to other publishers like Charlton, where he worked on the classic The Thing!, Tales Of The Mysterious Traveler and other titles. He worked for Charlton longer than any other company.

Ditko came to prominence before the birth of Marvel Comics as we know it, back in the late ’50s when it was known as Atlas. There he was an artist of quirky monster and outer space stories. More often than not the tales were plotted or scripted by Stan Lee, thus allowing the artist almost complete freedom to shape the story as he saw fit. Ditko, unlike some, found this to be liberating and allowed his imagination to run wild, creating self-contained universes full of inherently good people with flaws.

Comic books published by Marvel in their pre-super hero days were anthologies, consisting of a lead story, usually by Lee and Kirby, then fillers by Ditko, some of which outshone the lead stories. When he wasn’t pencilling, Ditko inked for Kirby, and in inking Jack’s pencils, showed himself to be a highly sympathetic inker, one of “The King’s” best.

Ditko recalled in 1966:

“Just one 20-page story every four weeks means the writing and lettering have to be taken into account. I generally pencil five pages a day (I like four). The inking depends on how soon I get the story back after it’s lettered. I can wait a week or as long as three weeks. I have to pencil stories a lot differently that I naturally do when I do my own inking. For myself, I draw in line, or outline, sketchy in many areas, rarely putting in darks unless for a certain mood, and even then it’s just a slight indication. I like drawing with the brush – not just covering pencil lines with ink. Penciling for others – all lines must be definite, dark areas positive. Like a complete ink job but in pencil. That’s what it should be… I’ve never managed to do it.”

Ditko’s skills lay in his storytelling. As a penciller he was incredibly sympathetic to the writer/plotter, and as an inker he managed the rare skill of being able to enhance the pencils of an artist without overpowering the artist’s style with his own.

His Marvel work set the tone for Ditko’s career. He co-created Marvel’s flagship character, The Amazing Spider-Man (1961), along with Dr Strange (1963) and their respective casts. In this way Ditko was as influential upon the generations that followed him as Jack Kirby with his characters.

While at Marvel, Ditko continued to work for Charlton; his “campy” monster-movie titles Gorgo and Konga are still sought after and highly regarded by professionals and fans alike. There Ditko and writer Joe Gill created Captain Atom, a character that’s still prominent today at DC Comics (who bought the Charlton characters in the mid-1980s). Steve’s Charlton output included many short stories in horror anthologies like Haunted, Ghostly Tales, Ghost Manor, Ghostly Haunts, et al.

After leaving Marvel, Ditko brought his brilliance to DC, where he created fan-favorite The Creeper and the innovative Hawk And Dove, about two superhero brothers, one a fighter and the other a pacifist.

In 1967, Steve created his most personal, intellectual and controversial character. The fedora-and-suit-wearing vigilante with a blank-expression Facemask first appeared in issue 3 of artist Wally Wood’s “prozine,” Witzend, in a five-page story titled simply, “Mr. A.” (Ditko and Wood worked on various projects as penciller and inker and vice-versa.) Mr. A served as an outlet for Ditko’s staunch beliefs in Objectivism (“A is A”), a philosophy created by Ayn Rand (Atlas Shrugged, The Fountainhead). Ditko’s morally black-and-white character (who believes in only good and evil with no gray area between) appeared in several short b/w stories in various fanzines and alternative publications, including his own title. While working on Charlton’s Blue Beetle #1 the same year, Ditko created The Question, a faceless, fedora-wearing hero who, in Steve’s words, was a Comics Code-acceptable version of Mr. A.

For the rest of the 20th century, Ditko contributed to various publishers including Warren and a new version of Atlas, returned to DC (for whom he created Stalker and Shade, The Changing Man), then Marvel (most famously on ROM Spaceknight), plus smaller publishers like Eclipse/Renegade, ACE Comics, Fantagraphics, Dark Horse and others.

In 1988, Ditko teamed up with long-time friend and editor/writer Robyn Snyder (creator of the monthly historical industry ‘zine The Comics) to produce Steve’s personal work and characters. Snyder has published Ditko’s comics and short essays ever since, with most of this century’s endeavors as Kickstarter projects, all of which consistently reach more than their funding goals. Despite not working on mainstream superheroes for decades, Steve’s fans and true supporters are still numerous and loyal.

As for those whom Ditko influenced, the list is long and illustrious. The second and third waves of Marvel artists such as Jim Starlin, Frank Brunner, Alan Weiss, John Byrne, Paul Smith, Art Adams, Walter Simonson, Frank Miller and many others have all paid homage to Ditko in their work, as have writers such as Gerry Conway, who helped build upon the Ditko universe. Even today Ditko’s influence can be seen in Spider-Man and Dr Strange comics as artists find that nobody drew those characters quite like he did.

Even more impressive is that Steve Ditko, once he walked away from mainstream comics, never returned to the corporate-owned characters that he created. He refuses to allow them to define him, instead creating more new universes to play in. He remains an iconoclast, a true individual, and the man against whom many use as a measuring stick to compare themselves. But, as many will say, you can compare an artist to Ditko, but they’ll never better him.

He does not attend conventions or give interviews. One of the last of the latter was in 1966, where Ditko offered advice to the next generation of artists:

“You must really understand the basics of art – perspective, composition, anatomy, drapery, light and shade, storytelling, etc. You need a solid foundation of what is right and good to build on. You can’t really draw anything well unless you understand the purpose of that drawing (storytelling), the best way to get the drawing across (individual point of view – composition), and convincingly (perspective, anatomy, drapery, light and shade). Until I came under the influence of Jerry Robinson, I was self-taught, and you’d be amazed at the hours, months, and years one can spend practicing bad drawing habits. Jerry gave me a good foundation, but I have to constantly watch out; bad drawing habits are hard to kill. Practicing on a solid, proper foundation, you train your hand and mind to work like a unit while correctly broadening your knowledge and ability. Spend more time practicing the things you find most difficult to do, not what is easy or you like. Keep eliminating the problems. Study, draw life around you – people, drapery, and reality. Study other artists to see how they interpret reality to art. Study and compare your art to others and reality – not copying, either, but interpreting it the way you think best. No one is an original artist; no living artist today or yesterday invented or discovered art, brushes, ink, paper, or comics. Everyone builds on what was done before or is being done (whether it’s a shoe, a light bulb, an airplane, or a drawing). In art, the artist interprets in his own individual way; he plays up more of or less of: uses more or less of what others have built. He can stress constant over natural action. A comical approach or a serious one. A lot of fine lines or bold lines; detailed or plain. Use line-pattern textures or solid and straight black and white. Any mixture of all there is. His style or “originality” is just his individual interpretation. If you draw a scene the way you personally think it should be, rather what this or that artist did with a similar scene or might do, you will have your own “original” style. After all, there’s really no one else in the world just like you.”

That advice is just as pertinent today as it was nearly fifty years ago.

(All Ditko quotes taken from Rapport #2)

Article written by Daniel Best with Mike Pascale, December 2015.